NOTE: This post is part 3 in a series addressing concepts found in the 2009 Horizon Report. Part 1 can be found here. Part 2 can be found here.

In this series of posts, I’ve discussed blogs being used as personal web publishing systems and explored ways educators might use Web2.0 tools, originally designed for ‘personal’ use, to instead work with students to build knowledge together. It probably goes without saying that one of the key aspects of the World Wide Web is that it’s all (potentially) connected – but until a few years ago, these ‘connections’ were at best accomplished by creating hyperlinks to other sites and content, and later by smarter search engines. With technologies like RSS feeds, however, the Web 2.0 world has made it easier to link, share, and re-purpose content. We have increasing ability to view and publish content in any style/format/design we choose.

The web is continuing to spill over from our computers to all of our other everyday gadgets, including our music players, televisions, and radios – in some cases, even our refrigerators. On the Map of Future Forces Affecting Education (created by the KnowledgeWorks Foundation and the Institute for the Future) this concept is described as ‘The End of Cyberspace’ and is listed as one of of the key ‘Drivers of Change’ in the coming years:

“Places and objects are becoming increasingly embedded with digital information and linked through connective media into social networks. The result is the end of the distinction between cyberspace and real space.”

Cellphones+laptops = ‘mobile devices’

We’ve all heard the hype about the growing number of cellphones being used worldwide. Recent statistics for China, for example, show 616 million mobile phone users vs. 253 million Internet users. The web is huge, to be sure, but the costs associated with bringing ‘computers’, as we think about them in the traditional sense, to the world’s populations are significant [see, for example the troubles related to the One Laptop per Child project]. No doubt given the need for such devices to be mobile, have longer battery life, and be more affordable, small mobile devices, in particular cellphones, have become the main and/or only access tool for the web and web-based data for many people.

As cellphones continue to get ‘smarter’, recent laptop trends suggest that mobility, connectivity and price are more important to consumers than actual processing power. New, ‘mini’ laptops – commonly called ‘netbooks’ are often small enough to fit into a large purse or small bookbag – they’re extremely light, have longer than average battery life, and are fairly powerful. They’re also extremely popular – according to Gartner, netbooks will move nearly 21 million units in 2009, even as sales of full-size laptops and particularly desktop computers continue to decline. Netbooks generally have smaller hard drive space than we might be used to – that’s because they’re intended to be used to pull and access content from the ‘cloud’. Want to write a document? Connect to the web and use Google Docs. Update your Facebook profile or Twitter status. Use Pandora to listen to music, or YouTube to watch video (or access a site like Hulu to watch ‘television’ instead of turning on a TV – a growing trend in itself). Access your files and notes using an online service like Evernote or Dropbox. For more info on the netbook revolution, see Clive Thompson’s informative article in Wired.

iPhones and eReaders: the web – reshuffled

The iPhone represents a milestone in this connection between the web and mobile devices. The iPhone is known for its web-accessing ‘apps’, and the mobile phone market has reacted by focusing less on voice communications devices that simply enable email or simple text, and more on devices that can access and accommodate all the content that the ‘real’ web has to offer. Just this week, Duke released an iPhone app that enables searching course info, contacts, maps and more.

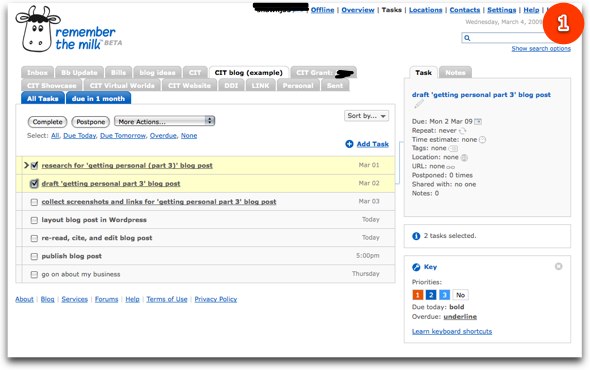

Here’s an example of how an iPhone app leverages info from the web. Remember the Milk (RTM) is a small ‘to do list’ or ‘getting things done’ application that I use to create checklists for myself to better manage tasks. I can access RTM on the web (see #1 below), but I can also email tasks to RTM, use Twitter to send, receive and manage tasks [see #2 below), or, better yet, use my iPhone to access the info stored on the RTM website via the iPhone RTM app (see #3 and #4 below). In many ways, I actually prefer the iPhone app, in that its somewhat more uncluttered, and focuses on the task (no pun intended) at hand rather than ‘wowing’ me with excessive design elements.

Another recently hyped technology – the Amazon developed ‘eReader’ device known as the Kindle (recently updated) was originally marketed as a sort of ‘iPod’ for books. The Kindle’s real appeal is that it can pull in text from the web – stretching well beyond books. You can now read the NY Times on the Kindle, on the web, on paper (which, by the way, apparently costs more – much more – than sending every reader a Kindle), or even on the iPhone or another mobile device that can pull in an RSS feed. Because the Kindle caters first to the most traditional of media consumers, good old school ‘readers’, it tends to legitimize content from the web for the non-web user. You wouldn’t pay $2 a month to read Gizmodo on the computer, but you might to get it downloaded conveniently to your Kindle every day. (Pesonally, I find the cost of these subscriptions excessive – but Amazon has the corner on the eReader market right now. The point is that many people are willing to pay for access, convenience, and format even if it’s for a convenience or access that already exists in other forms that they perhaps just don’t know about and/or understand).

Conclusion: (re)Educating the Networked World

The implications of some of these trends and technologies, for those of us working in education, are pretty obvious. The Kindle, and recent developments such as Google Book Search for mobile devices, bring up larger questions about the future of textbook publishing – and publishing in general. Beyond text, there’s also a growing world of photos, video and other audio/visual artifacts that practically demand the ability to be viewed, shared and/or re-purposed.

For all the hype attributed to social networking sites like Facebook – the real hype is that people want to be connected and re-connected – that people want the ability to quickly share, discuss, and update. An awareness of these technologies – and of the cultural shifts that social networking technologies create – is really what’s required to leverage them for learning. It’s not a question of “how do we pipe syllabi and course lists into Facebook” as much as: what can be learned and done with all of these people so complexly connected?

Mimi Ito, writing about the MacArthur sponsored report “Living and Learning with New Media: Summary of Findings from the Digital Youth Project,” looks at how networked life might trigger a shift in education where the personal and the public continue to blur:

Youths’ participation in this networked world suggests new ways of thinking about the role of education. What, the authors ask, would it mean to really exploit the potential of the learning opportunities available through online resources and networks? What would it mean to reach beyond traditional education and civic institutions and enlist the help of others in young people’s learning? Rather than assuming that education is primarily about preparing for jobs and careers, they question what it would mean to think of it as a process guiding youths’ participation in public life more generally. (via Ito’s blog)

Michael Blanding’s article “Thanks for the Add. Now Help Me with My Homework,” also explores this concept of social participation:

“Educators studying social networking sites are just beginning to develop ways to use them to teach social issues. Indeed, the biggest gift of social networking sites is the same thing that makes them such a danger — the immediate ability to interact with so many strangers so different from themselves. “A lot of social justice depends on acknowledging the legitimacy of someone else having the same rights as you do,” says Dede. “If it turns out that, gee, people very different than me are also very like me in some ways, that doesn’t automatically lead to a respect for others, but it can help with that and with a skilled teacher building those connections.”

The following Common Craft-style video, “The Networked Student” (created by Wendy Drexler’s high school class), does a great job illustrating several ways social networking sites and tools might be (and in many cases, currently are) used for education.